BBC

BBCLegend has it Bernard Shabangu’s grandfather, Bhobho, once speared down a lion that was terrorising his community in Mpumalanga, a province in eastern South Africa. The story goes that the lion was so fearsome that even the white people who had guns would run away when it roared.

“One day, my grandfather is said to have walked up the hill where the lion was roaring with his spear and shield,” says Bernard. “The lion charged at him, but my grandfather speared him to death and was made Headman for his bravery.”

As a Headman, or traditional leader, Bhobho owned cattle and land. Then one day in the mid-1950s, it was all taken away from him with no compensation under a law introduced in 1950 called the Group Areas Act. This stated that South Africa’s apartheid government could choose certain areas to be used by a single race.

In the early 1990s, democratic South Africa’s new constitution allowed for land taken from black farmers to be returned to them. But it did so with great care and the setting-up of new cross-community partnerships were encouraged.

In this spirit, when Bernard, now 48, and his community decided to reclaim their land, they agreed to work in partnership with the white farmers who had been working on it.

“We did not say we want the white folks to leave,” says Bernard. “They are here, they are working with us, they are supporting us… we are saying that partnership is what’s going to take this country forward.”

Mayeni Jones

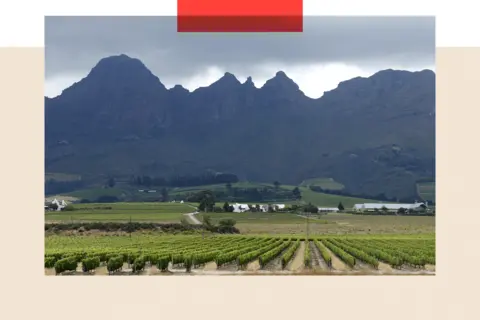

Mayeni JonesToday, the Matsamo Communal Property Association and its partners employ over 2,000 people from the local community and is the country’s biggest exporter of lychee to the US. It also grows papayas, sugar cane and bananas for local supermarkets. Matsamo has been hailed as an example of what successful land reform can look like in South Africa.

But for some in the country, progress on land reform has been too slow. In January, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed into law a bill that allows, in some circumstances, land to be seized by the state without compensation.

Opponents argue it is a threat to the principle of private ownership. And among those opponents is Donald Trump. He has said the new bill was “hateful rhetoric” towards “racially disfavored landowners.”

Mr Trump said he would pause all aid to South Africa, which could be worth around $320m (£253m) according to the US Agency for International Development. Some worry he might eventually exclude South Africa from a trade agreement, estimated by the office of the US trade representative to be worth $14.7bn (£11.6bn) a year.

The challenge facing Rampahosa is a knotty one: can he find a way to speed up land reform to appease his political friends and foes, without losing one of the country’s biggest trading partners?

A risk to property rights

Three and a half hours’ drive west of the Matsamo CPA, near the town of Ermelo, is the farm of Lion du Plessis. He is an Afrikaner farmer, a descendant of Huguenots who once fled France. He works and lives on the farm his grandfather acquired in the 1970s. He grows maize and soybeans, as well as rearing sheep and cattle. His farm is spread across a thousand lush and green hectares with a serene lake in the middle of it.

“I was born on this farm, I grew up here and I’ve been farming since 2012,” he tells me in the middle of one of his fields.

For Lion, the new expropriation act threatens property rights and is a risk for farmers.

“Expropriation is not a problem if there’s compensation, but the compensation must be just and fair and equitable.”

He argues that without private property rights, farms such as his won’t be able to borrow money.

“If you put a tool like this in the government’s hands, where they can just take land, or take any property for that matter, it is not economically viable to invest in South Africa.

“In agriculture we need private property in order to access capital, we need to borrow money from the banks or from agricultural corporations to cover our costs. And if we don’t have private property rights, we won’t be able to get money and to get capital.”

Mayeni Jones

Mayeni JonesThe impact the bill could have on foreign investment is also of concern to AfriForum, a group that seeks to protect the rights of Afrikaners.

“We know that international investors, if they hear the term “no compensation”, and you give that power to many state organisations, what they call an expropriation authority, then it will deter investment,” its CEO Kallie Kriel tells me.

But for Bernard these laws are a careful attempt to address long-standing unfairness. He insists: “Land reform in South Africa is not going to be a vulgar land grab. What the president is proposing is a constitutionally-managed process of land reform for the public good, to say black and white people in South Africa must share in the land that is there.”

Addressing historic inequalities

Professor Ruth Hall from the Institute for Poverty, Land, and Agrarian Studies of the University of the Western Cape argues the issue of access to land in South Africa dates back to before the start of formal apartheid in 1948.

“If we think about the history of South Africa, this is what we can call a settler colony. It was a colony in which large numbers of European settlers, over many centuries, came and settled, displacing indigenous people,” she says.

By the end of the 19th Century, most of the land that is currently South Africa had been taken over by white people.

The Natives’ Land Act of 1913 defined less than one-tenth of South Africa as Black “reserves” and prohibited any purchase or lease of land by Blacks outside the reserves.

She says the subsequent Group Areas Act only reinforced the division and further reduced economic opportunities for black people.

Reuters

ReutersProf Hall calls it “structural apartheid geography” and explains that this is “very much intact,” today. She describes how even though there is a growing black middle class in South Africa, there are still fundamental problems for the majority of black South Africans “who either do not have access to well located land in the cities or who live in rural areas without secure rights.”

Agriculture remains one of the main sources of economic revenue for the country, but the majority of commercial agricultural land is still in the hands of the white minority which makes up around 7% of the population.

Reuters

ReutersThere is an ongoing debate as to whether the no-compensation clause breaches section 25 of the constitution, which establishes property rights for all South Africans.

Kallie Kriel thinks the bill is rife for abuse. He says: “Actually, any reason can be used by the expropriating authority, which can be a corrupt or radical municipality.”

But land lawyer Bulelwa Mabasa, who was on a panel that advised President Cyril Ramaphosa on land reform, thinks that there are “sufficient safeguards” and says it’s clear when expropriation can take place: “There is a very heavy burden that is placed on the expropriation authority to have reports from different departments, justifying the need for the expropriation in the first place, and justifying the need for expropriation without compensation.”

A mission unfulfilled

In 1996, the South African government launched its land reform programme, promising to settle all claims for redistribution by 2005 and to redistribute 30% of white-owned commercial agricultural land to black South Africans by 2014.

The fact neither target has been met helps explain the pressure for last month’s toughened-up legislation.

Prof Hall explains: “There’s a mandate on the state that it must actually redistribute land. It must deal with historical claims to land.”

AfriForum has conceded that no large-scale land seizures have taken place and that the majority of land still remains in the hands of the white minority.

But balancing the obligation to redistribute with property rights was never going to be straightforward.

Trump and Musk weigh in

And now the debate around land ownership has gone beyond the borders of South Africa due to the recent intervention of US president Donald Trump, who issued an executive order on 7 February, just two and a half weeks after being sworn into office. The order claimed the expropriation act would “enable the government of South Africa to seize ethnic minority Afrikaners’ agricultural property without compensation”.

The executive order claimed the act was part of a number of discriminatory policies and “hateful rhetoric” towards “racially disfavored landowners”.

The American President also accused Pretoria of taking aggressive positions towards the United States and its allies, including accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and strengthening its ties with Iran.

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockAs a result of these actions, Trump said he would pause all aid to South Africa and offered to resettle all “Afrikaner refugees escaping government-sponsored race-based discrimination”.

South Africa’s case against Israel is seen by some as evidence it supports Hamas, in addition to the close ties it maintains with Iran.

“South Africa is trying to maintain its alliance with North America and Europe, while at the same time building its relationship with its partners in the global South,” says Prof Hall. “In my view, South Africa’s attempt to play both sides in an increasingly polarised world is what is really at play here.”

Reuters

ReutersTrump is not the only figure in his administration to have taken an interest in South Africa’s internal affairs. So too has Elon Musk, who’s been tasked with managing government efficiency in the US. Musk, who was born in Pretoria, has been trying to license his Starlink telecommunications business in South Africa.

But under the country’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policy telecom firms are required to have 30% ownership by black people. Musk called BEE “racist”. Currently, only 3% of the country’s top companies are controlled by black South Africans.

A blunt tool?

Every year, the US president reviews which African countries should continue to be part of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). It allows some African countries to export goods to the US duty free and is credited with creating thousands of jobs across the continent, including in South Africa.

But now there are fears Donald Trump’s promise to cut all “future funding to South Africa” may see South Africa excluded.

Doing so may, however, be a bit of a blunt tool – Prof Hall points out that coming out of AGOA would ironically disproportionately affect the white farmers Donald Trump says he wants to protect.

“I can assure you that most white farmers are far more worried about this punitive act on our trade deal with the US than they are about land expropriation,” she said.

Can the circle be squared?

So can the South African government, and President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ANC specifically, satisfy those who believe further land reform is a must without being frozen out economically by the US and losing foreign investors?

One job is to work out what is really driving Donald Trump. Nomvula Mokonyane, Deputy Secretary General of the ANC, does not believe this is solely about the issue of land and thinks South Africa’s position over Israel may well be the driver.

She says: “Our view is that we need to let our government engage the American administration, so that then we understand whether are we dealing with the issue of the expropriation of land, or are we dealing with many other issues… related to Palestine and so on and so forth.”

The signing of the expropriation bill comes in the context of the ANC finding itself in a coalition with other parties for the first time, and it may be trying to signal to black voters that it’s still willing to fight for their rights.

After Mr Trump’s funding freeze, Mr Ramaphosa said South Africa will not be bullied in his state of the nation address earlier this month. It’s one of the few positions that all his coalition partners appear to agree with.

Prof Hall does not detect much possibility of any kind of u-turn on the new law. She says: “We have said very clearly the Expropriation Act is a law that was passed by a democratic parliament. He has signed it into law, which is his obligation as state president.”

South Africa is already feeling the effects of US’ diplomatic pressure: both the US secretary of state and the treasury secretary have refused to join their counterparts at this month’s G20 meetings hosted by South Africa. And there are concerns Donald Trump could also be absent from the leaders’ summit later this year.

President Ramaphosa has promised to send envoys to the US and other countries to explain his country’s positions on the expropriation act, the war in the Middle East, as well as some of its other foreign policy decisions.

Whether South Africa can soften the current hostility coming from Washington, without compromising on its national priorities is a huge test for this fledgling democracy.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Leave a Reply