BBC

BBCAbby Wu was just 14 when she had cosmetic surgery for the first time.

After receiving hormone treatment for an illness, Abby’s weight increased from 42kg (6 stone 8lbs) to 62kg (9 stone 11lbs) in two months.

The change hadn’t gone unnoticed by her drama teacher.

“My teacher said, ‘You were our star but now you’re too fat. Either give up or lose weight fast,’” recalls Abby, who was preparing for her drama exams at the time.

Abby’s mother stepped in, taking her to get liposuction to remove fat from her belly and legs.

Abby remembers her mother’s words as she waited in the clinic in a hospital gown, nervous about the impending operation.

“Just be brave and walk in. You’ll become pretty once you’re out.”

The surgery was traumatic. Abby was only given partial anaesthesia and remained conscious throughout.

“I could see how much fat was extracted from my body and how much blood I was losing,” she says.

Family handout

Family handoutNow 35, Abby has gone on to have more than 100 procedures, costing half a million dollars.

She co-owns a beauty clinic in central Beijing and has become one of the most recognisable faces of China’s plastic surgery boom.

But the surgeries have come at a physical cost.

Sitting in front of a mirror inside her luxury duplex apartment in Beijing, she gently dabs concealer onto bruises from a recent face-slimming injection – a procedure she undergoes monthly to help her face appear “firmer and less chubby” after three jaw reduction surgeries removed too much bone.

But she insists she has no regrets about the surgeries and believes her mother made the right decision all those years ago.

“The surgery worked. I became more confident and happier, day by day. I think my mum made the right call.”

Abby Wu

Abby WuOnce seen as taboo, plastic surgery has exploded in popularity over the last 20 years in China, fuelled by rising disposable incomes and shifts in social attitudes, in large part driven by social media.

Every year, 20 million Chinese people pay for cosmetic procedures.

Overwhelmingly, it is young women who seek surgery. Eighty per cent of patients are women and the average age of someone receiving surgery is 25.

While appearance has always been important in Chinese culture, particularly for women, beauty standards in the country are changing.

For years, the most sought-after features were a blend of Western ideals, anime fantasy and K-Pop inspiration: The double eyelid, the sculpted jawline, the prominent nose, and the symmetrical face.

But lately, more disturbing procedures are on the rise – chasing an unrealistic, hyper-feminine, almost infantile ideal.

Botox is now injected behind the ears to tilt them forward, creating the illusion of a smaller, daintier face.

Lower eyelid surgery, inspired by the glassy gaze of anime heroines, widens the eyes for an innocent, childlike look.

Upper lip shortening narrows the space between lip and nose, thought to signal youth.

But much of this beauty is built for the screen. Under filters and ring lights, the results can look flawless. In real life, the effect is often uncanny – a face not quite human, not quite child.

TikTok

TikTok SoYoung

SoYoungCosmetic surgery apps like SoYoung (New Oxygen) and GengMei (More Beautiful) – claiming to offer algorithm-driven analysis of “facial imperfections” – have been surging in popularity.

After scanning and assessing users’ faces, they provide surgery recommendations from nearby clinics, taking a commission from each operation.

These and other beauty trends are shared and promoted by celebrities and influencers on social media, rapidly changing what’s considered desirable and normal.

As one of China’s earliest cosmetic surgery influencers, Abby has documented her procedures across major social media platforms and joined SoYoung soon after it launched.

Yet despite having undergone more than 100 procedures, when she scans her face using SoYoung’s “magic mirror” feature, the app still points out “imperfections” and suggests a long list of recommended surgeries.

“It says I have eye bags. Get a chin augmentation? I’ve done that.”

Abby seems amused.

“Nose-slimming? Should I get another nose surgery?”

Unlike typical e-commerce sites, beauty apps like SoYoung also offer a social media function. Users share detailed before-and-after diaries and often ask superusers like Abby for their advice.

‘My skin felt like there was cement underneath’

To meet surging demand, clinics are opening up rapidly across China.

But there’s a shortage of qualified practitioners and large numbers of clinics are operating without a licence.

According to a report by iResearch, a marketing research firm, as of 2019, 80,000 venues in China were providing cosmetic procedures without a licence and 100,000 cosmetic practitioners were working without the right qualifications.

As a result, it’s estimated that hundreds of accidents are happening every day inside Chinese cosmetic surgery clinics.

Dr Yang Lu, a plastic surgeon and owner of a licensed cosmetic surgery clinic in Shanghai, says in recent years the number of people coming for surgeries to repair botched operations has been growing.

“I’ve seen many patients whose first surgery was botched because they went to unlicensed places,” Dr Yang says.

“Some even had surgery inside people’s homes.”

Yue Yue, 28, is among those to have surgery that went badly wrong.

In 2020 she received baby face collagen injections – designed to make the face appear more plump – from an unlicensed clinic opened by a close friend. But the fillers hardened.

“My skin felt like there was cement underneath,” she says.

Desperate to undo the damage, Yue Yue turned to clinics she found through social media – well-known names – but the repairs only made things worse.

One clinic attempted to extract the filler using syringes. Instead of removing the hardened material, they extracted her own tissue, leaving her skin loose.

Another clinic tried lifting the skin near her ears to reach the filler underneath, leaving her with two long scars and a face that looked unnaturally tight.

“My entire image collapsed. I lost my shine and it’s affected my work [in human resources for a foreign company in Shanghai] too.”

She found Dr Yang through SoYoung last year and has since undergone three repair surgeries, including for her eyelids which were damaged during a previous operation by another clinic.

But while Dr Yang’s surgeries have brought visible improvements, some of the damage from the botched procedures may be permanent.

“I don’t want to become prettier any more,” she says.

“If I could go back to how I looked before surgery, I’d be quite happy.”

‘It ruined my career’

Every year, tens of thousands like Yue Yue fall victim to unlicensed cosmetic clinics in China.

But even some licensed clinics and qualified surgeons aren’t following the rules strictly.

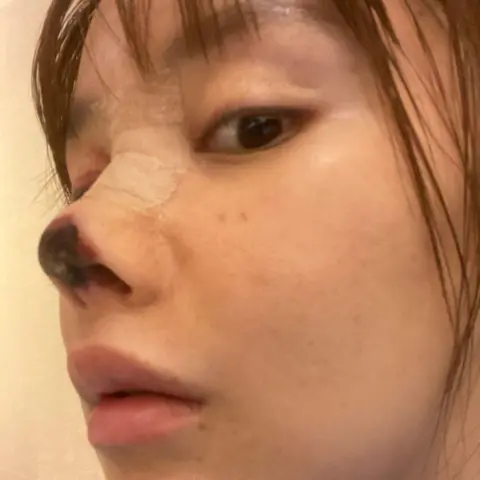

In 2020, actress Gao Liu’s botched nose operation – in which the tip of her nose turned black and died – went viral.

“My face was disfigured and I was very down. It ruined my acting career.”

She had received the nose surgery at a licensed Guangzhou clinic called She’s Times from Dr He Ming, who was described as its “chief surgeon” and a nose surgery expert.

But in reality Dr He was not fully qualified to perform the surgery without supervision and had not obtained his licensed plastic surgeon status from the Guangdong Provincial Health Commission.

Authorities fined the clinic, which closed soon after the scandal, and barred Dr He from practising for six months.

However, weeks before She’s Times was officially dissolved, a new clinic, Qingya, requested to register at the same address.

Gao Liu

Gao LiuBBC Eye has found strong links between She’s Times and Qingya, such as the same Weibo account and the retention of several staff, including Dr He.

The BBC has also learned that Dr He only obtained the licensed plastic surgeon qualification in April 2024, even though he was technically barred from applying for the status for five years from the date he was sanctioned in 2021.

Qingya now claims to have opened 30 branches.

Dr He, Qingya and Guangdong Provincial Health Commission did not respond to the BBC’s requests for comment.

The Chinese Embassy in the UK said: “The Chinese government consistently requires enterprises to operate in strict compliance with national laws, regulations, and relevant policy provisions.”

Four years and two repair operations later, Gao Liu’s nose remains uneven.

“I really regret it. Why did I do it?”

China’s Central Health Commission has been trying to crack down on the issue of under-qualified health practitioners performing tasks beyond their expertise in recent years – including ordering local health bodies to improve regulation and issuing stricter guidelines – but problems persist.

From job offer to debt and surgery – within 24 hours

In today’s China, looking good is important for professional success.

A quick search on popular job recruitment platforms reveals many examples of employers listing physical requirements for roles, even when they have little to do with the actual work.

One receptionist role asks for candidates to be “at least 160cm tall and aesthetically pleasing”, while an administrative job demands “an appealing look and an elegant presence”.

And now that pressure is being exploited by a growing scam in some Chinese clinics in which vulnerable young women are offered jobs, but only if they pay for expensive surgeries carried out by their would-be employers.

Da Lan, not her real name, applied for a “beauty consultant” job at a clinic in Chengdu, south-western China, on a popular recruitment website in March 2024.

After the interview, she was offered the position that same evening.

But she says when she began her role the next morning, she was taken to a small room by her manager, who scanned her up and down and gave her an ultimatum – get cosmetic work done or lose out on the job.

Da Lan says she was given less than an hour to decide.

Under pressure, she agreed to undergo double eyelid surgery – priced at over 13,000 yuan (£1,330) – more than three times the monthly salary of the role – with more than 30% annual interest.

She says staff took her phone and used it to apply for a so-called “beauty loan,” falsifying her income details. Within a minute, the loan was approved.

By noon, she was undergoing medical tests. An hour later, she was on the operating table.

From job offer to debt and surgery – all within 24 hours.

The surgery did nothing for her job prospects. Da Lan says her manager belittled her, shouting her name in public and swearing at her.

She quit after just a few weeks. Looking back, she believes the job was never real.

“They wanted me to leave from the beginning,” she says.

Despite having worked there for more than 10 days, she was paid only 303 yuan ($42). With help from her friends, Da Lan paid off the debt for her surgery after six months.

BBC Eye spoke to dozens of victims, and met three including Da Lan in Chengdu, a city that has set out to become China’s “capital of cosmetic surgery”. Some have been trapped in much larger debt for years.

The clinic Da Lan says scammed her had previously been reported by other graduates and exposed by local media, but it remains open and is still recruiting for the same role.

This scam isn’t limited to clinic jobs – it’s creeping into other industries.

Some live-streaming companies pressure young women to take out loans for surgery, promising a shot at influencer fame.

But behind the scenes, these firms often have undisclosed agreements with clinics – taking a cut from every applicant they send to the operating table.

In a bohemian-style café in Beijing, the perfect setting for a selfie, Abby meets her friends for coffee.

The trio adjust their poses and edit their faces in great detail – extending eyelashes and reshaping their cheekbones.

When asked what they like most about their facial features, they hesitate, struggling to name a single part they wouldn’t consider altering.

The conversation turns to chin implants, upper-lip shortening, and nose surgery.

Abby says she’s thinking about another nose job – her current one is six years old – but surgeons are finding it difficult to operate.

“My skin isn’t as stretchable after so many procedures. The doctors don’t have much to work with. You can’t give them enough fabric for a vest and expect a wedding dress.”

The metaphor lingers in the air, underscoring the toll taken by all of the operations.

But despite everything, Abby has no plans to stop.

“I don’t think I’ll ever stop my journey of becoming more beautiful.”

Leave a Reply